|

Information

Results

Get Involved

Resources

|

|

Executive Summary - CT2011

|

|

|

CarbonTracker 2011

CarbonTracker 2011 is the sixth release of the NOAA CO2 measurement and modeling system. CarbonTracker is designed to keep track of sources (emissions to the atmosphere) and sinks (removal from the atmosphere) of carbon dioxide around the world, using atmospheric CO2 observations from a host of collaborators. The current release of CarbonTracker, CT2011, provides global estimates of these surface fluxes of CO2 from January 2000 through December 2010.

Notice: methodological changes

CarbonTracker 2011 is a unique release due to the use of

multiple models to provide flux prior guesses. Details are below.

Estimates of CO2 sources and sinks over North America

From 2001 through 2010, ecosystems in North America have

been a net sink of 0.7 ± 1.3 PgC yr-1 (1 Petagram Carbon equals 1015 gC, or 1 billion metric ton C, or

3.67 billion metric ton CO2).

This natural sink offsets about one-third of the

emissions of about 1.9 PgC yr-1 from

the burning of fossil fuels in the U.S.A., Canada and

Mexico combined (Figure 1).

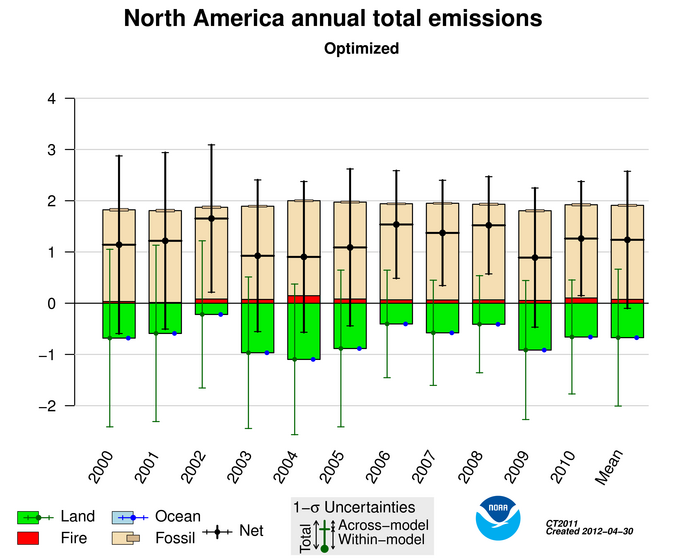

| Figure 1. Annual total emissions from North America. The bars

in this figure represent CO2

emissions for each year in PgC yr-1 from the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico combined. See map on this page.

CarbonTracker models four types of surface-to-amosphere

exchange of CO2, each of which

is shown in a different color: fossil fuel emissions

(tan), terrestrial biosphere

flux excluding fires (green), direct emissions from

fires (red), and air-sea gas

exchange (blue).

Negative

emissions indicate that the flux removes CO2 from the atmosphere. The net

surface exchange, computed as the sum of these four

components, is shown as a thick black line.

|

Whereas fossil emissions are generally steady over

this period, ranging between 1.8 and 1.9 PgC yr-1, the amount of CO2

taken up by the North American biosphere varies significantly from

year to year. In terrestrial biosphere models, inter-annual

variability in land uptake can be related to anomalies in large-scale

temperature and precipitation patterns. While the CarbonTracker

period of analysis is relatively short compared to the dynamics of

slowly-changing pools of biospheric carbon, episodes of extremes in

net ecosystem exchange (NEE) have been associated with climatic anomalies (see e.g. Peters et al., 2007). It is interesting to note

that the inferred year-to-year variabilty (the "range") of land uptake

is actually as big as the mean sink itself.

The year with the smallest annual uptake by terrestrial ecosystems in North America

was 2002, when there was widespread drought in the U.S. west. During

this year, land ecosystems accounted for a sink of only 0.2 PgC yr-1. This reduced land sink is largely responsible

for 2002 being the year in the CarbonTracker record with the largest

input of CO2 to the atmosphere from North

America, when net emissions reached 1.7 ± 0.6 PgC yr-1.

In contrast, our observing system did not detect an effect from the

2007 drought in the U.S. Southeast. This is likely due to

lack of coverage of the area (Figure 3) in our current

observing network. New observations in CT2011 compared

to CT2009, however, do lead to interesting differences in

this region for 2008. For CT2011 in 2008, the U.S. Southeast

represents a distinct source of carbon dioxide to the

atmosphere, whereas CT2009

fluxes for this same place and time are equivocal.

In CT2011, we find that 2003, 2004, and 2009 were the years with the largest North American land

sink, with ecosystems taking up about 0.9 - 1.1 PgC yr-1—a land sink that is about 36% bigger than the average. Fossil

fuel emissions from North America were also slightly reduced in 2009

compared to earlier years as a result of the economic

downturn. As a result, ecosystems removed about half of fossil fuel emissions over North America in 2009, and this was the year with the lowest net input of

CO2 to the atmosphere from North America.

This 2009 net annual emission was 0.9 ± 1.4 PgC yr-1, about 25% smaller than the average of 1.2

± 1.1 PgC yr-1. This is the

first year since the beginning of the CarbonTracker record in 2000 for

which the net flux from North America has fallen below

1 PgC yr-1.

Spatial distribution of surface fluxes

CarbonTracker flux estimates include sub-continental patterns of

sources and sinks coupled to the distribution of dominant ecosystem

types across the continent (Figure 2). We have greater confidence in

countrywide totals than in estimates of regional sources and sinks,

but we expect that such finer-scale estimates will become more robust

with future expansion of the CO2 observing

nework. Our results indicate that the sinks are

mainly located in the agricultural regions of the Midwest

(36%), deciduous forests along the East Coast (33%), and

boreal coniferous forests (17%).

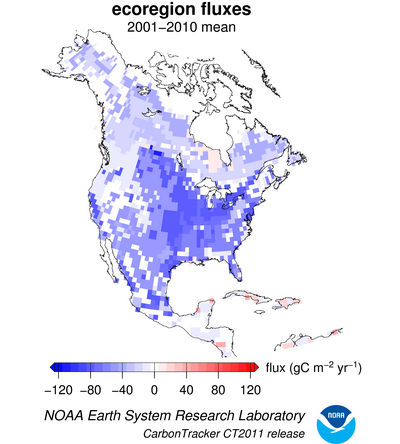

| | Figure 2. Mean ecosystem fluxes. The

pattern of net ecosystem exchange (NEE) of CO2 of the land biosphere averaged over

2001-2009, as estimated by CarbonTracker. This NEE

represents land-to-atmosphere carbon exchange from

photosynthesis and respiration in terrestrial ecosystems,

and a contribution from fires. It does not include fossil

fuel emissions. Negative fluxes (blue colors) represent

CO2 uptake by the land

biosphere, whereas positive fluxes (red colors) indicate

regions in which the land biosphere is a net source of

CO2 to the atmosphere. Units

are gC m-2 yr-1.

|

Word of caution about high-resolution biological flux maps

Figure 2 shows estimated fluxes by ecoregion.

While we also provide flux maps and data with a finer

1° x 1° spatial resolution, for example

on our flux maps pages, these

ecoregions define the actual scales at which

CarbonTracker operates. With the present observing

network, the detailed one-degree fluxes should not be

interpreted as quantitatively meaningful for each block.

Any within-ecoregion patterns come directly from results of the terrestrial

biosphere model.

Part of this high-resolution patterning comes from variations of

temperature, precipitation, light, plant species, and

soil type over each ecoregion. To spread the influence

of measurements from the sparse observation network,

CarbonTracker makes adjustments uniformly over an entire

ecoregion.

These adjustments scale the net ecosystem flux of CO2 predicted by the terrestrial

biosphere model by the same factor across each ecoregion.

Thus we caution that the 1° x 1°

spatial detail in CarbonTracker land fluxes is based on

the simulations of the terrestrial biosphere model and

the assumption of large-scale ecosystem coherence. This

has not been verified by observations.

The CarbonTracker observing system

CarbonTracker

surface flux estimates are optimally consistent with

measurements of ~36,100 flask samples of air from 81

sites across the world, ~33,900 four-hourly averages of

continuously measured CO2 at 13

sites (10 in North America, plus observatories at Mauna

Loa, Hawaii; Barrow, Alaska, South Pole; and American Samoa), and

~15,100 four-hourly averages from towers at 9 locations

within the continent (see Figure 3). Eight of these

towers sample air from heights more than 100m above

ground level.

|

|

Figure 3. CarbonTracker 2011 Observational Network Click on any site marker for more information. Double-click on a site marker to center the map on that site.

|

Calculated time-dependent CO2 fields throughout the global atmosphere

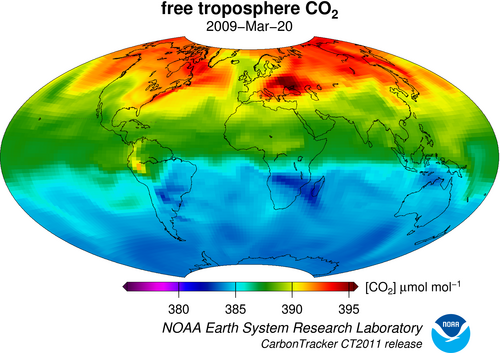

A "byproduct" of the data assimilation system, once

sources and sinks have been estimated, is that the mole fraction of

CO2 is calculated everywhere in

the model domain and over the entire 2000-2010 time

period, based on the optimized source and sink estimates (Figure 4).

As a check on model transport properties and CarbonTracker inversion performance, calculated

CO2 mole fractions are regularly

compared with measurements of ~31,000 air samples taken by

NOAA/ESRL at 26 aircraft sites, which are not used in the

estimation of optimized sources and sinks.

Since CarbonTracker simulates CO2 throughout the entire atmospheric

column, the model atmosphere can be sampled exactly like

satellite retrievals of CO2.

Such estimates are generally more sensitive to the CO2 mole fraction in some parts of the

atmosphere than in others, and by using a vertical profile

of this sensitivity, a direct analog of the satellite

estimate can be constructed.

|

|

Figure 4. Carbon dioxide weather

Shown is the daily average of the pressure-weighted mean mole fraction of carbon dioxide

in the free troposphere as modeled by CarbonTracker for March 20, 2009. Units are

micromoles of CO2 per mole of dry air

(μmol mol-1), and the values are given by

the color scale depicted under the graphic. The "free troposphere" in

this case is levels 6 through 10 of the TM5 model. This corresponds to about 1.2km above

the ground to about 5.5km above ground, or in pressure terms, about

850 hPa to about 500 hPa. Gradients in CO2

concentration in this layer are due to exchange between the atmosphere

and the earth surface, including fossil fuel emissions, air-sea

exchange, and the photosynthesis, respiration, and wildfire emissions

of the terrestrial biosphere. These gradients are subsequently

transported by weather systems, even as they are gradually erased by

atmospheric mixing.

|

Flux uncertainties

It is important to note that at this time the uncertainty

estimates for CarbonTracker sources and sinks are

themselves quite uncertain. They have been derived from

the mathematics of the ensemble data assimilation system,

which requires several educated

guesses for initial uncertainty estimates. The

paper describing CarbonTracker (Peters et al. (2007),

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. vol. 104, p. 18925-18930)

presents different uncertainty estimates based on the

sensitivity of the results to 14 alternative yet

plausible ways to construct the CarbonTracker system.

For example, the 14 realizations produce a range of the

net annual mean terrestrial emissions in North America of

-0.40 to -1.01 PgC -1

(negative emissions indicate a sink). The procedure is

described in the Supporting Information Appendix to that

paper, which is freely downloadable from the PNAS web

site.

Furthermore, the estimates do not take into

account several additional factors noted below. The

calculation is set up for sources and sinks to slowly

revert, in the absence of observational data, to first

guesses of net ecosystem exchange, which are close to

zero on an annual basis. This set-up may result in a

bias. Also due to the sparseness of measurements, we

have had to assume coherence of ecosystem processes over

large distances, giving existing observations perhaps an

undue amount of weight. The process model for

terrestrial photosynthesis and respiration was very

basic, and will likely be greatly improved in future

releases of CarbonTracker. Easily the largest single

annual mean source of CO2 is

emissions from fossil fuel burning, which are currently

not estimated by CarbonTracker. We use estimates from

emissions inventories (economic accounting) and subtract

the CO2 mole fraction signatures

of those fluxes from observations. As a result, the

biosphere and ocean fluxes estimated by CarbonTracker

inherit error from the assumed fossil fuel emissions.

While these emissions inventories may have a small

relative error on global scales (perhaps 5 or

10%), any such bias translates into a larger

relative error in the annual mean ecosystem sources and

sinks, since those fluxes have smaller magnitudes. We

expect to add a process model of fossil fuel combustion

in future releases of CarbonTracker. Finally, additional

measurement sites are expected to lead to the greatest

improvements, especially to more robust and specific

source/sink results at smaller spatial scales.

Consistency of modeled and observed atmospheric CO2 growth rates

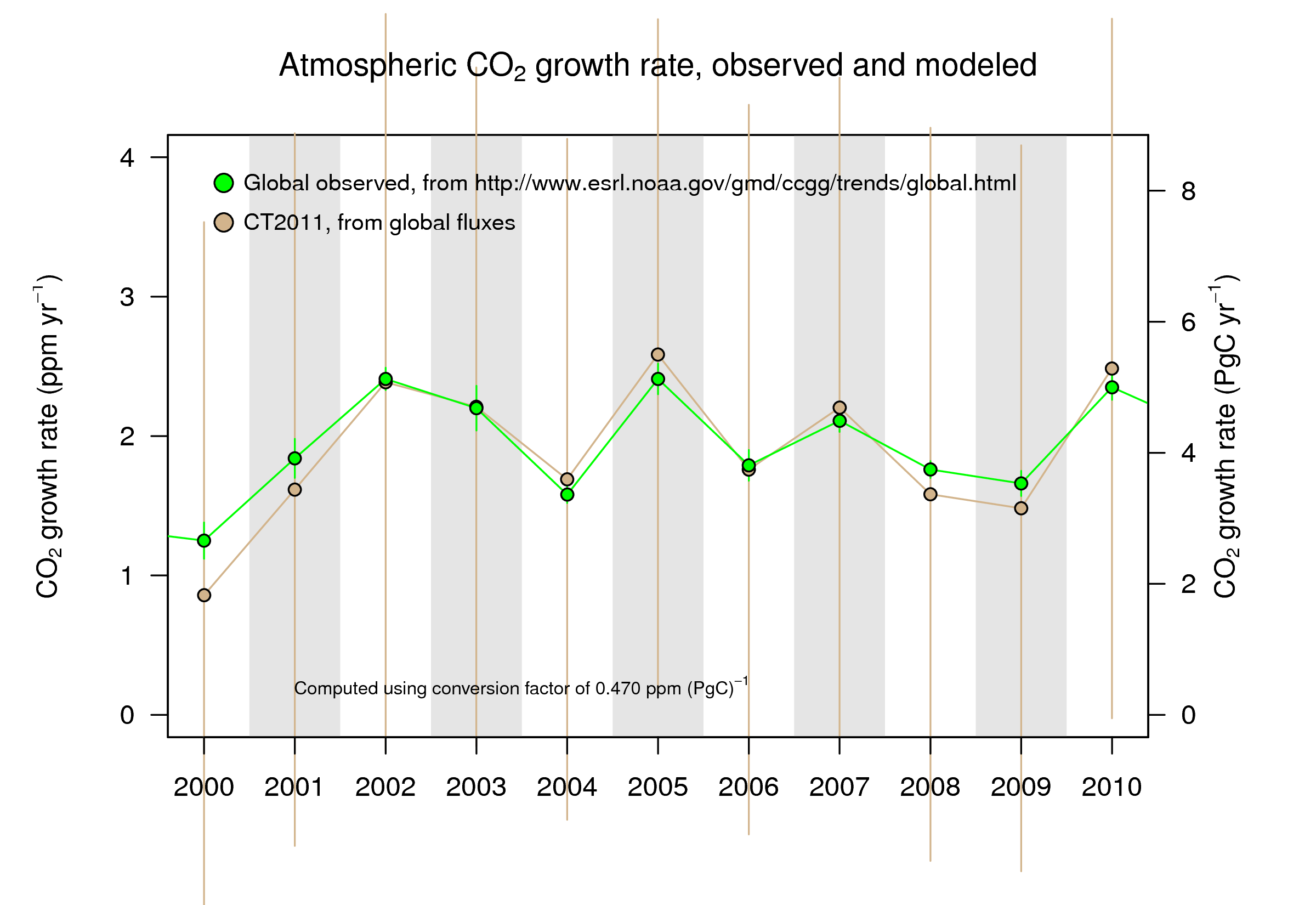

Global atmospheric CO2 growth

rates inferred directly from observed carbon dioxide at marine surface sites are

consistent with those modeled by CarbonTracker, both in their average

values and in their year-to-year variations (Figure 5). These global

growth rates continue to hover at around 4 PgC yr-1, or around 1.9 ppm yr-1 (Figure 5). The 2009 growth rate modeled by

CarbonTracker was below average at 3.4 ±

3.1 PgC yr-1. This was not due to

a significant decrease in fossil fuel emissions, as can be seen from

estimates of

global fluxes used in CarbonTracker. Instead, the most notable difference for the 2009

atmospheric growth rate appears to be reduced biomass burning fluxes

from the tropics

and southern hemisphere, which at 1.4 PgC yr-1 are about 0.5 PgC yr-1 below their 2001-2009 mean of

1.9 PgC yr-1.

| | Figure 5. Atmospheric CO2 growth rates. Observed atmospheric CO2 growth rates (source: NOAA ESRL page on global trends in CO2) are plotted against the atmospheric CO2 growth rate inferred from CT2011 global fluxes. Note that error bars on the observed growth rates are relatively small and may not be visible on this plot. |

|

CT2011 methodological differences

CT2011 uses multiple "priors", or first-guess surface fluxes of

CO2. In the CarbonTracker inversion system,

first-guess fluxes are modified by comparison with observed

atmospheric CO2 mole fractions. In any such

Bayesian estimation system, the final flux result reflects, to some

extent, influence of the prior. To evaluate the impact of the prior

estimate on our final estimated fluxes, we have conducted eight

independent simulations, each of which uses a unique combination of

flux priors. This factorial design uses two different fossil fuel

emissions estimates, two land biosphere models, and two air-sea

exchange models. We report here a statistical summary of that

collection of simulations. Importantly, the reported uncertainty

incorporates differences computed from this suite of eight independent

simulations. Further information on the multi-model analysis is

available in the CT2011

documentation.

Unlike CT2010, this release of

CarbonTracker is a full reanalysis of the 2000-2010 period.

Details of these methodological differences are presented

in the "What's New?" page and

the CT2011 documentation.

|

|

CarbonTracker is a NOAA contribution to the North American Carbon Program

|

|