Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders Heritage Month: A Conversation with Field Operations Chief Gataivai “Vai” Talamoa

May 27, 2021

In honor of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders (AANHPI) Heritage Month, Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML) is highlighting the great work done by our Field Operations Liaison Gataivai Talamoa (known as “Vai”) at the American Samoa Observatory (SMO) and NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC).

SMO is one of four baseline observatories around the world that focus on monitoring long-term and global-scale changes in background atmospheric constituents, with minimal impact from direct human influences. This includes focus areas such as the global carbon cycle and greenhouse gases, aerosols, solar radiation, ozone, halocarbons, and other trace species.

Every year, GML appoints a NOAA Corps Officer to serve as the station chief of SMO and the NOAA Corps Officer would serve 11-12 months in American Samoa. Vai has been serving as a field operations liaison at SMO since 2012 to help bridge the transition between appointments and provide cultural and traditional protocol orientation, and operations and logistics support for station chiefs.

Due to the travel restriction of COVID-19, our new appointee Lieutenant Junior Grade (LTJG) Ryan Musik wasn’t able to arrive at American Samoa in time. Vai stepped in to serve as the acting station chief and single-handedly ran the observatory for 8 months since the last station chief left in October 2020. Ryan was finally able to arrive at American Samoa in late April 2021 and the turnover between Ryan and Vai was complete in May 2021.

Highlighting Vai’s career path so far and his great works as the PIFSC Field Operations Chief and GML Continuing Station Chief, our conversation follows.

What did you do before coming to NOAA? I grew up as a farmer in American Samoa, where you farm on the mountains and fish the streams and ocean of American and Independent Samoas’. Thus, all I learned was farming science and engineering. In the 1970s, I joined the U.S. Navy. Back then, military admission tests would offer free buffets, and some of my friends and I went together for the buffet, not so much the test. However, I happened to pass the test my first time and this started my service life with the U.S. Navy until I retired and entered federal government services. First I worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, then transferred to the Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare Systems, and finally to NOAA PIFSC, my current employer.

I started as an aviation electrician’s mate (AE), a source rating for the U.S. Navy Flight Engineer program and I underwent a very adventurous career traveling around the world. I started my higher education with Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, obtained my first degree, a Bachelor of Science, from the University of Phoenix, and later an MBA degree at the University of Phoenix Tucson Campus at the closing of my military service with the U.S. Navy.

All the leadership, management, sciences, technology, engineering, and mechanics/math knowledge I gained throughout my military career and service to the country, and the educational value of all that training, I now adapt to accomplish the objectives of my civilian life.

How did you come to work for NOAA? What is your current role?

After retiring from the U.S. Navy, I was hoping to do something completely different. Also, I wanted to come back to American Samoa to spend as much time with my mom who was 93 years old, and fulfill my duties to her as a son, a chief, and servant to our family before she left us.

In 2012, the opportunity with GML arose and it aligned well with what I want - doing science while providing good services to my community. NOAA GML and Fisheries formed a partnership merging the position of field operation/logistics management specialist and GML electronic technician. My job is to work for both GML and the NOAA PIFSC to help staff for both departments overcome logistical and operational challenges in our small community. American Samoa is an isolated duty location where all operational and logistical materials, supplies, and equipment arrive via surface vessel or aircraft. The partnership also provided both departments the opportunity to improve relationships between all NOAA departments with programs, projects, and services in American Samoa with the people of Samoa through a strong school and village-based outreach program.

I went into my interview with a limited understanding of the equipment and global monitoring, but I made the point that if I don’t know the answer to a question, I will go find the answer and learn the “how-to” on the spot. Several months later, I finished my training in Colorado and started my role in American Samoa.

Right now, I am the Field Operations Chief at the PIFSC SOD American Samoa Field Office. My role has evolved over these years. I came aboard as the PIFSC SOD Representative/Liaison. The office was new and as the wrinkles were worked out the position grew to become the PIFSC SOD Field Operations/Logistics Management Specialist. GML was folded in under the watch of Observatory Station Chief Ms. Christina Hammock; now NASA Astronaut Christina Hammock Koch and has for the past nine years evolved to provide logistic support and serve as a doorway for any NOAA department and other federal agencies that conduct scientific research or any other program, project or service in the Samoa Archipelagos.

What is a typical day working at SMO like?

At SMO, we launch ozone data collection balloons every week, sample aerosols, help users from different departments collect data, and fix and maintain equipment. Normally, the station chief is responsible for most of the hands-on work 6 days a week and I would cover one day so they could take a break. Because Ryan’s arrival was delayed by the COVID-19 conditions, I covered the role of the station chief for the past eight months.

The observatory is situated on the northeastern tip of Tutuila Island, about a 1.5-hour drive from the American Samoa Field Office in Pago Pago, where the station chief and I reside. While most data are collected at the observatory, ozonesonde balloons are launched at the weather station near the Field Office. At the observatory, instruments like the Dobson spectrometer that collects ozone data and the nephelometer that measures aerosols run continuously. We also collect flask samples of air to provide a baseline for greenhouse gases.

A lot of my work is to make sure we get the right things at the right time. It might seem easy at first sight, but this is actually challenging. In American Samoa, there are only two ways to get things in - aircraft or surface vessel, so shipping time is often long and unpredictable. Because of COVID-19, managing logistics has become even more challenging.

It is also difficult to buy hardware because we only have two hardware stores. A few years back we only had farmer’s markets on the island. The lack of availability also means that things we can get here might have a different quality than they are at other locations, so we have to learn to work around these challenges.

Are there other works you do with PIFSC? What are those like?

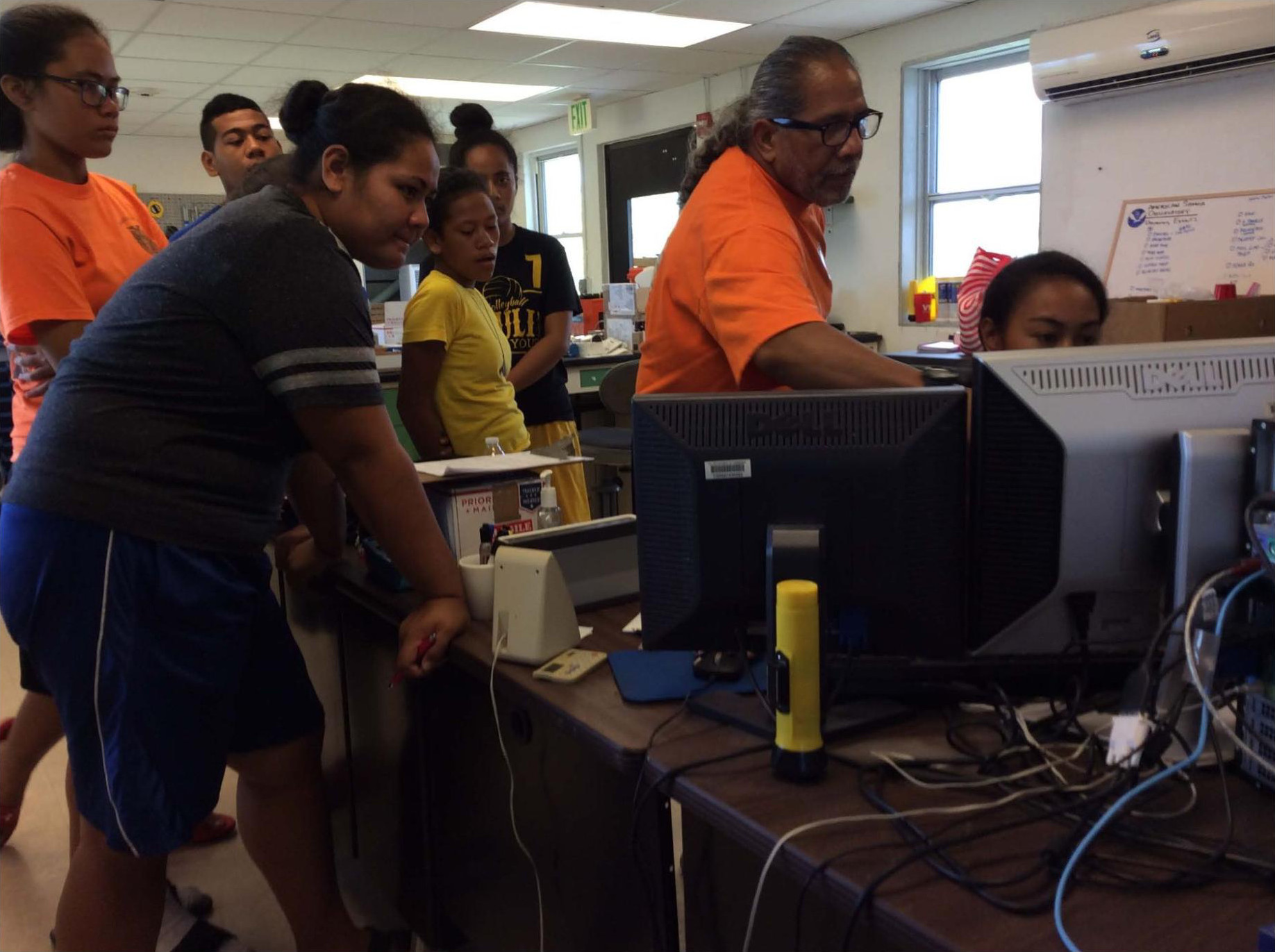

I also do a lot of outreach work. We often have students come over to the Field Office after school. We provide them the opportunity to use computers and the internet. This is quite unique because 95% of the students in American Samoa don’t have access to the internet, while 80% of them don’t even own an electronic device.

Because the location of the Field Office is quite remote from everything else, students can focus on doing their homework or developing science projects under our guidance. For example, my students are developing a model that shows how people would live if American Samoa became completely underwater due to sea-level rise.

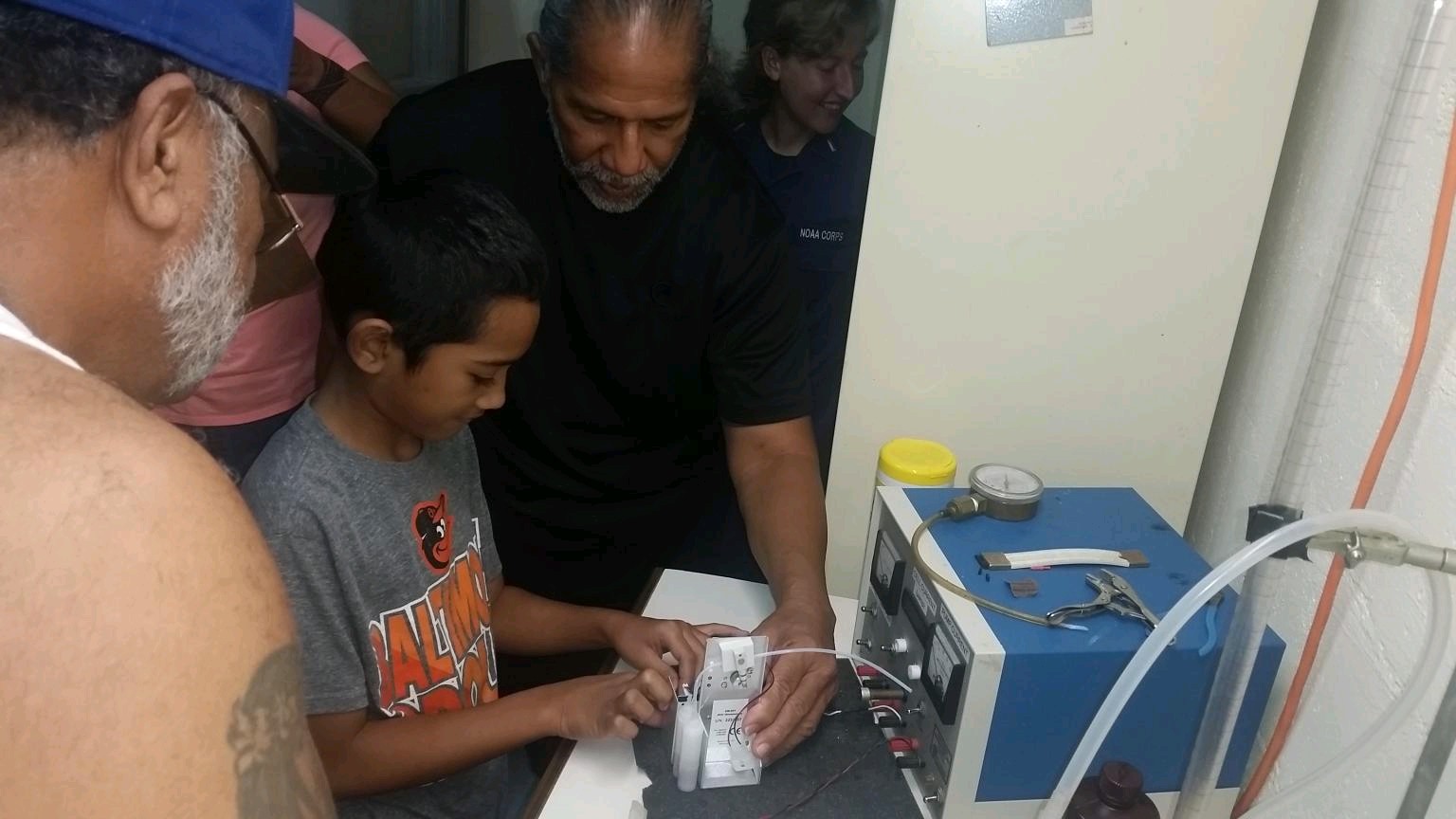

In addition to the after-school program, we also host science camps for children. These camps usually have 200 children attending, but now due to the COVID condition, we reduce it to 40. I teach them about the observatory during these camps.

Other outreach works I do are community focus. I organize marine debris clean-ups with local communities every other week. We often collect 200 to 300 bags of trash and most of it is styrofoam. Occasionally, I will bring a portable unit to the village and launch an ozone balloon there. It is a really fascinating experience for people to look at the monitor and see the changes of ozone across the atmosphere in real-time. This helps to make an abstract term more real for them.

What do you enjoy and value most about your work?

I really enjoy the outreach programs that bring our work to the community. American Samoa has a very different culture - it is very people and family oriented. We run with a chief system that revolves around family and extended clans of kinship. There are between several hundred to thousands of people led by each chief and we gather at the chief’s house every Sunday. People look up to the Chief and develop to become useful to the community.

I am the High Chief for my family. My special role allows me to deliver NOAA’s message to the chief’s council and my community without offense. Here in American Samoa, we experience climate change in action, but people might think that it is just weather. It is very important to create more awareness. When we share our knowledge, we mean more to them, and they also mean more to us.

What is your plan for the next steps?

In the long run, I am definitely interested in going back to school again and studying environmental science or biology. I am looking to study something that can tie the rising sea level, farming, and freshwater systems together. Climate change and rising sea levels are very real concerns in American Samoa. To compound that, the island has also sunk by roughly 0.5 inches per year due to the 2009 earthquake. These conditions threaten our freshwater system, which is an unsustainable resource that our farming practices rely on. I want to grow my knowledge in these topics and find solutions to the challenges faced by my people.